The Sydney School of Sculpture. Further Notes

In the nineteen seventies, when we were on top of the world and invincible as sculptors, we had measures in place to determine the success of our work.

We had independent judges, unaligned and principled, who supported clarity above loyalty. We were a machine, unparalleled, unequivocal. The standards established by our predecessors at The National Art School, namely Lynden Dadswell, Bertrand McKennell and Raynor Hoff were sketches for the sculptures we were making.

Our mission saw no limits.

We were The Sydney School of Sculpture which was without parallel anywhere. Nowhere was there such a sustained conversation about what sculpture had been, and what it could be. In the context of the long conversation about sculpture, this one hundred years extension of that discussion has continued and remains relatively unacknowledged.

The sculptors then were a sculpture family. Like with all families we laughed and loved, we argued and cried. We broke like families do. We formed allegiances that lasted and didn’t, then did again. Over fifty years there were many permutations available for different relations however the sculptural conversation continued.

Those of us then who were young have been joined by young sculptors now. Our program has exposed the folly of a generational zeitgeist. This business we mean is for all time and sculpture serves to slow an unsustainable flow of time. Even from within the group, some of us have died and this thing we are part of, is outside of us. It is its own animal.

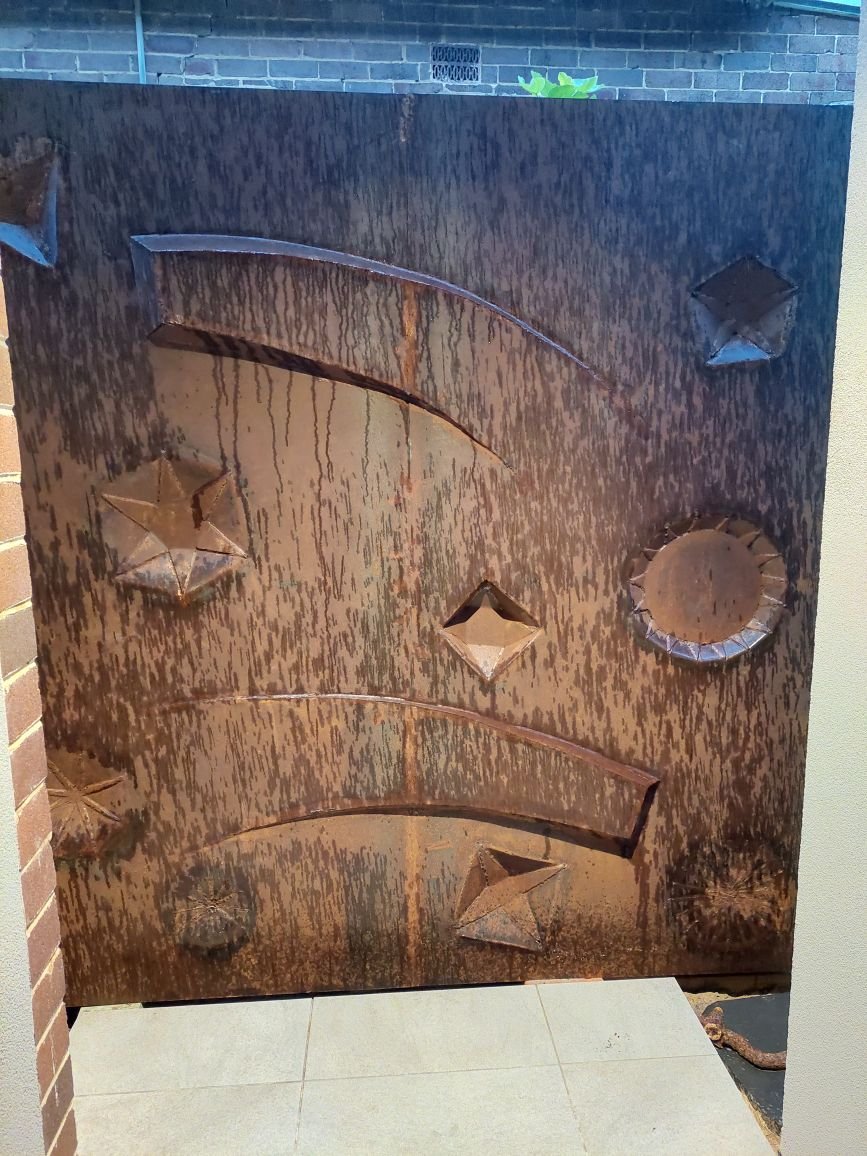

None of us much are in love with the material of choice. The shaping of steel makes us deaf and dirty. Neighbours shun us and even ask us to move away. When work is complete it is heavy to move, expensive even, which makes it not the darling of the curatorial profession, which is shaped by budget above taste.

The work we make is often big, too big for internal spaces, it is mostly placed outdoors where it is exposed to human and other nature. We remain sometimes too much a product of a particular appetite for large scale work inherited from American ambition. Some of us, many of us have adopted an appetite for a more sensible, modest scale. Watch this shrinking space!

For the community at large what has been consistent over fifty years is the appetite for material has been ‘anything at all’ so long as it is not steel! It is ironic, this ambivalence for steel when steel is the innocent bystander and is more the space divider. There is talk, art historically of ‘negative space’, when in fact what brings all the sculptors together in the sculptural language is the sharing of positive air.

It is air we share more than steel.

To recognise a work belongs to the SSS movement, it will be the shape of air you admire or despise, not the steel. The steel is the messenger. If you find yourself looking at the material of the sculpture rather than the air, it probably belongs to a different family of sculpture.