This speech was delivered for the launch of a new sculpture, Become The Part, which is a collaboration between my Daughter Agatha and myself. The sculpture is outside St. Andrews College, Sydney University, on the corner of Missenden Road and Carillon Avenue, Camperdown.

18 June 2022

Firstly, Agatha and I would like to say what a pleasure it has been to engage with the St Andrews community from our first meeting to today. I would especially like to thank Eleanor Cheetham for her very early enthusiasm for a collaborative work with Agatha and myself. Thanks too to Barbara Flynn, whose early contributions made the machinery turn. The broader college community, led by Wayne Erickson has proceeded to place no obstacles in the path to the realisation of that proposal.

Thank you, St Andrews.

The following statement is a quote from our initial proposal.

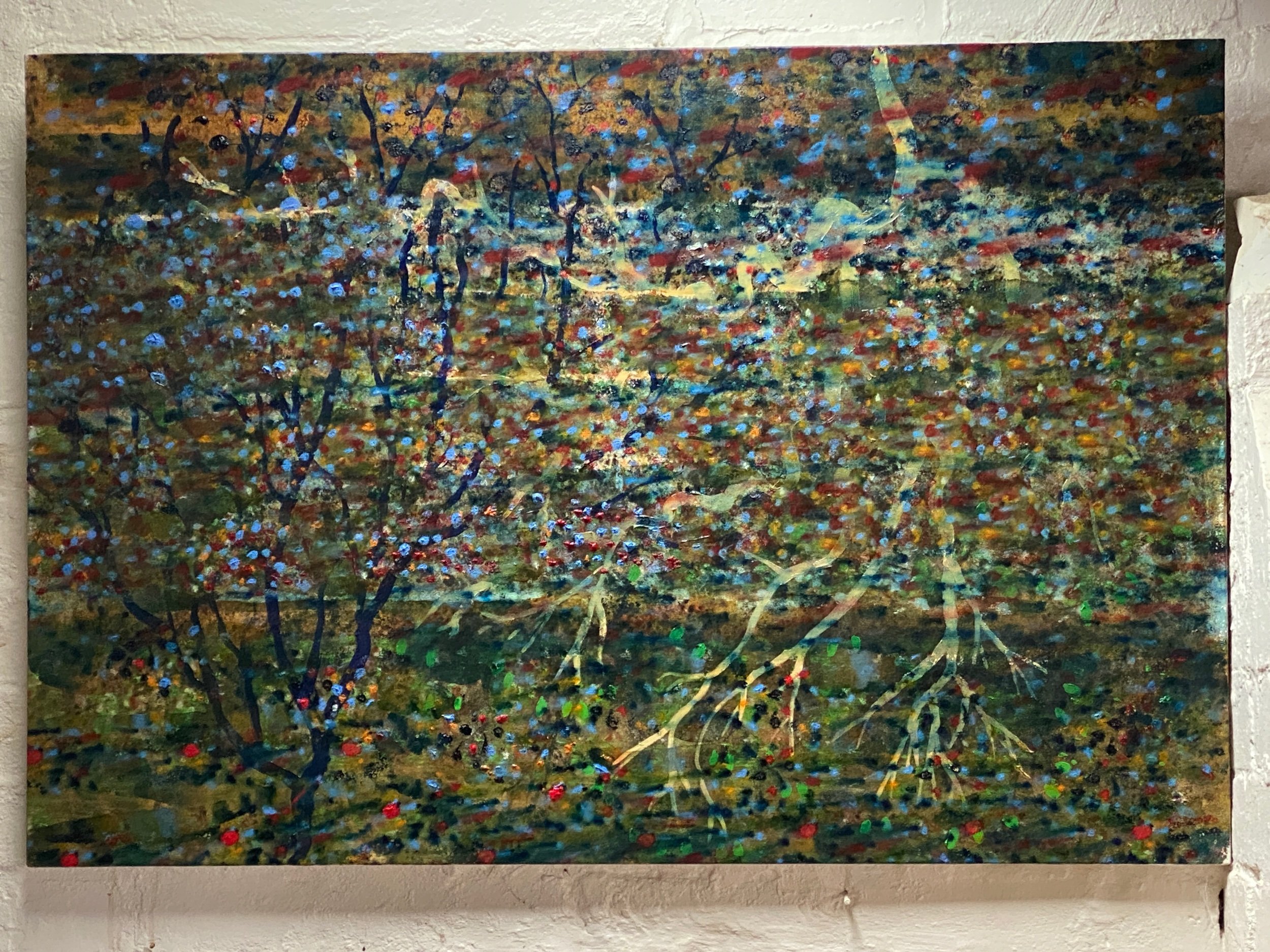

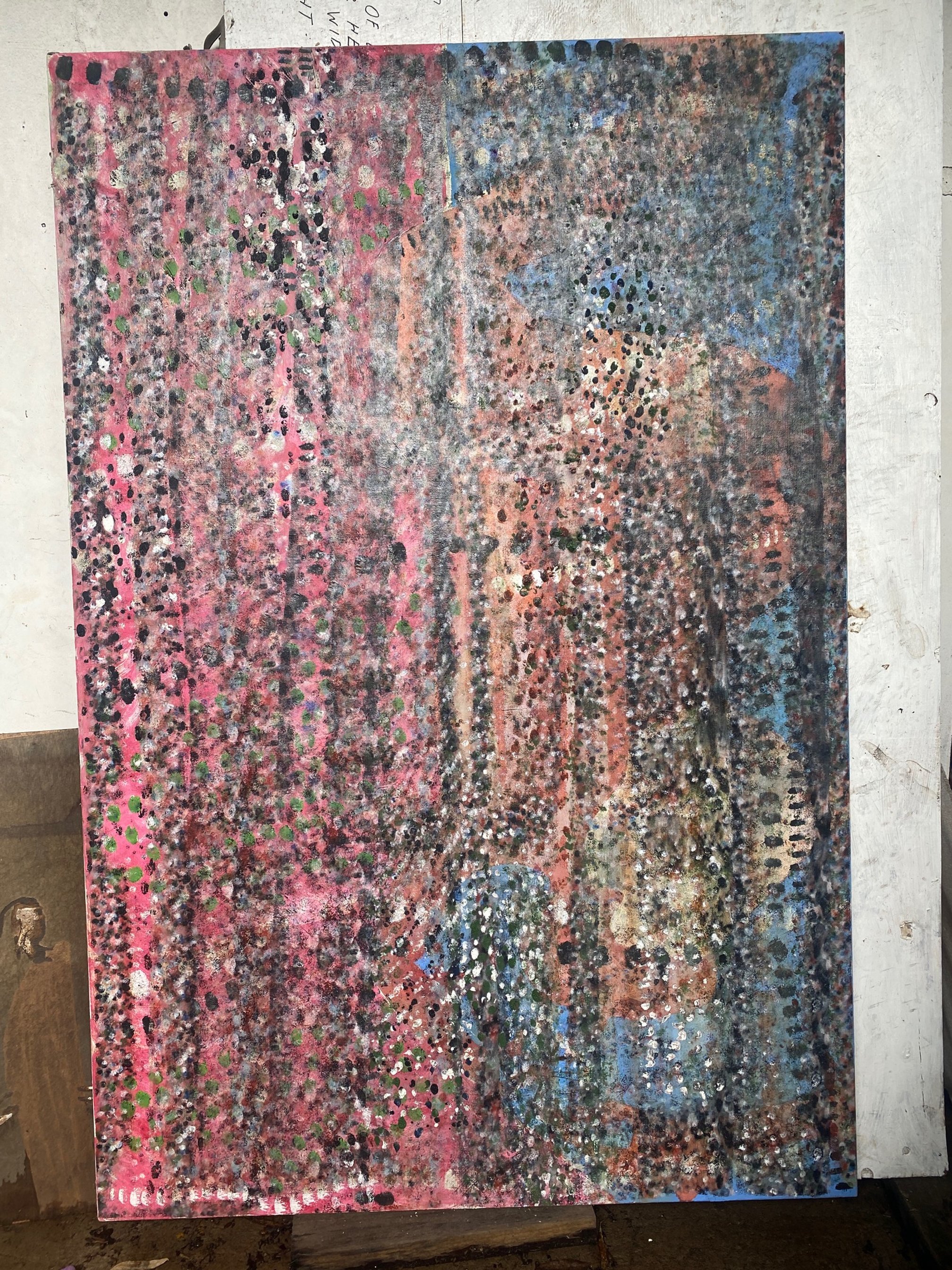

“This project will be our first formal collaboration. Our mutual influence and shared lineage will create a fertile ground for the process of making Become the Part. Bound by a common interest in the relationship between the opacity and transparency of poetic language; the formal manifestation of letterforms and an ongoing enquiry into the body’s relationship to the sculptural, Become the Part reflects a moment of cross-generational dialogue and play. Further, engaging with the college community as a father-daughter collaboration has enabled us to create a sense of familial intimacy with the college, and ask challenging and incisive questions of both each other and our commissioner.”

We can look back now from that early overview.

Despite the usual hiccups in executing commissioned works, there has been a smooth transition between first response and final execution. Lee Tunks, as The Man of Steel, has overseen the task of cutting, welding and bringing the parts together onto the site and not leave anything but Agatha’s and my mark. Martyn Rathbone and Marsupial, in the wet, have kept their humour to frame the work to Natalie McEvoy’s, Maria Martinez’ and more recently Phil Black’ FJMT’s landscape vision. Matthew Molder initially and Sam Wolff-Gillings from Spectrum have more broadly overseen all of the above. Douglas Knox from KPH has assured us that no part will tilt or drop or bend. Katrina Dunn-Jones from our team has steered Agatha and I through all the traffic and been there with us to enjoy the progress as it was made. Amanda Rowell from The Commercial Gallery who represents Agatha and Stuart Purves from Australian Galleries who represents me are here today to support their artists as they reliably do. Thank you everybody who has contributed.

***

Agatha can’t be here today. I can’t speak for her. Well, perhaps I can. We are all, at best, only a part of something bigger.

We can’t be anything unless we are buoyed and carried along by a current. A singular voice cannot be sustained.

The fact of the matter is that Agatha and I come from a long line of letter mongerers. We cannot help ourselves. My mother was a world renowned calligrapher and typographer. What we witness over our parent’s shoulders is what we become, for better and worse. We might like to justify what we do with immediate considerations however, mostly, what you get is what you are, we find.

My life personally, as a sculptor is the result of having given myself to the great history of Sydney sculpture over the last century. Collectively identified as The Sydney School of Sculpture, my voice is a small contribution to that history, that voice.

We are at a time when a singular pursuit has been found to be mostly problematic, destructive even in the wider world. From the singular pursuit of profit and gain we have seen the world come to a perilous place. Safe from danger is elsewhere in our thinking. We have to work together.

We are beginning to register the Indigenous voice that shows us how listening can be more productive than speaking. Listening occupies a shared space.

Sydney University is ready to open its arms to the world, not to hide behind its hallowed walls, but be more transparent. The new opening is the lungs through which the university can breathe new air.

The sculpture is more or less free-standing and placed on a corner, at a powerful intersection. The sculpture is framed by the landscaping and the voice of each gives to the other to make both voices audible. The sculpture itself is the product of a conversation between Sydney City Council and St. Andrews College.

The culture of St Andrews specifically, places emphasis on being part of a community. To not be a part is not to be strong and not belong.

From whichever perspective the words can be read, the already large words expand. They are wrought here from molten earth and through the letters you can walk, or rest, or take shelter. The walls of steel blend with the shapes of stone walls of the college, bringing the background forward into the shared space.

That ART as part of PART should find itself to have a final singular dedicated plate in this space is coincidental.

When things come together however, you don’t argue.

Wayne Erickson described the work as a ‘provocative’ sculpture by Agatha and me. The fact of the matter is that we are all in this together, so that whatever mischief or glory ensues, Agatha and I are happy to share.

Thank you.